May 2016

Words by Megg Minos

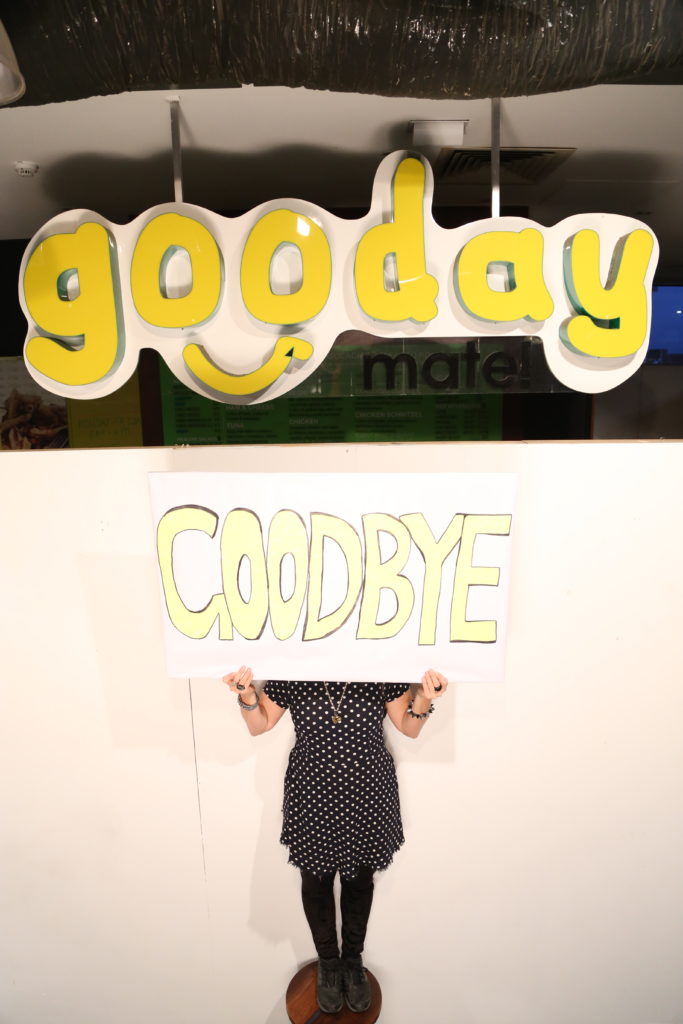

GOOday/GOOdbye – The Food Court 2013-2016

the people/the past/the present

The Food Court would like to acknowledge, with respect, the first people of this site.

Participating artists, board members and volunteers - with thanks:

Alesh Macak, Annee Miron, Ara Dolation, Amie Anderson, Birds A.R.I, Clare Walton, David Short, Geoffrey Barnett, Ian Stamp, Jonathan Homsey, Jessica Wilson, Kane Alexander, Laura Trist, Maria Miranda, Michele Donegan, Melissa Deerson, Minela Krupic, Megg Minos, Matteo Volpi, Michael Burrowes, Miles Green, Mark Johnstone, Nico Reddaway, Sasha Margolis, Siying Zhou, Sammy Besley.

Founding member James Wright was offered use of the space in 2013; this

gesture was made possible through the program of urban revitalisation

headed by Marcus Westbury of Renew Australia.

Along with several other artists - Polly Stanton, Matt Tierney, David Short and Nico Reddaway; the Food Court was occupied – the site that had indeed been a food court, complete with KFC and juice bars was now a multi-disciplinary art wonderland.

Over the course of the first year, various members moved on, drawn by

residencies in foreign lands, further study and work. The nature of the ARI is irrepressible.

Amie Anderson became involved in early 2013 and in the absence of the

other original members; she and Nico Reddaway formed a close working

relationship and took on most of the responsibilities of running The Food Court.

Over the last three years have been supported by other creative practitioners; who have maintained an interest in the space as exhibitors, performers and as a migratory flock of board members as well as Renew Australia and Docklands Spaces.

unfolding chambers

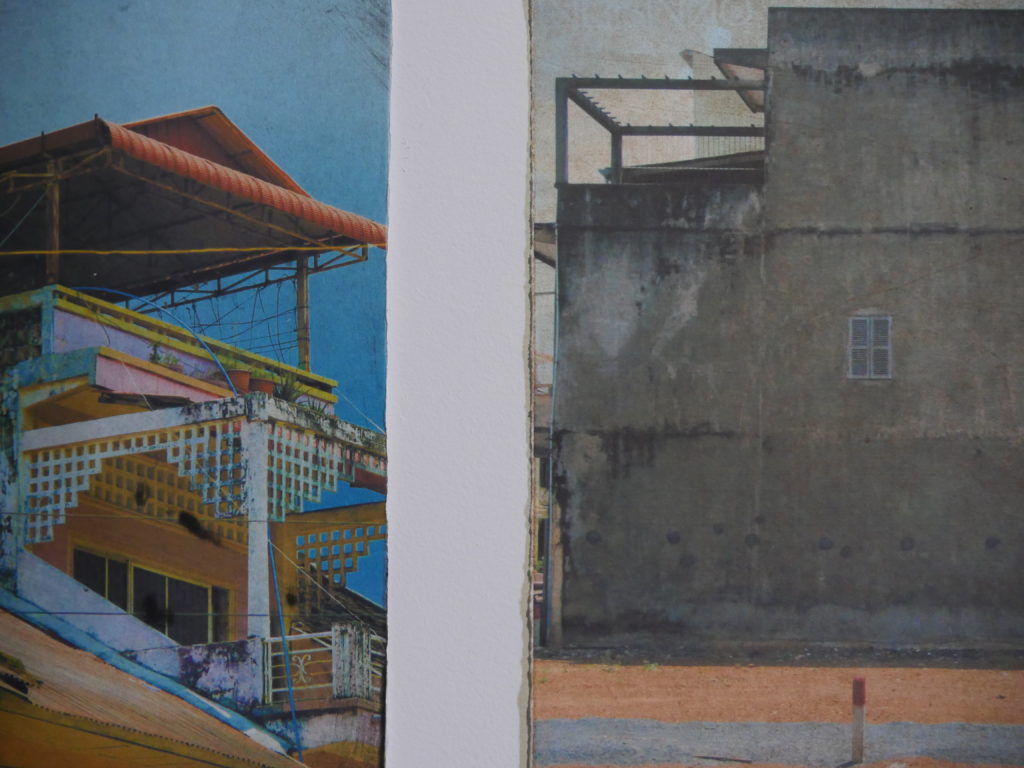

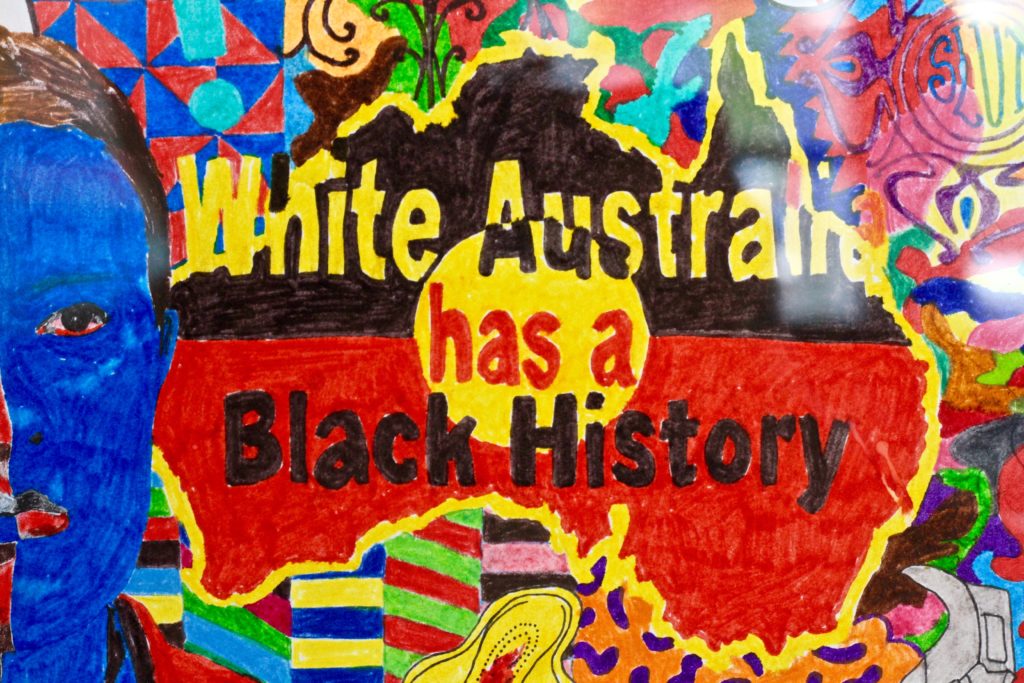

The Docklands is a marginal site, a fringe of high-rise residential towers, franchise businesses and a medley of restaurants and bars on the edge of a city that has fewer spaces to expand into.

It is an environment that was developed so quickly and with such

determination to lock capital into physical space, that the thought of multi-generational inhabitants, creative classes or cultural diversity has been lost in the forward momentum of development.

Of the pre-existing post-colonial cultural identity (architectural and social) there is little evidence in the way that the site presents. Of the pre-colonial geological and social environment there is no evidence – no faux-natural recreated ecologies to indicate what was on the site before. The waterways have been straightened, deepened, widened. The large bluff at the edge of the site, at Spencer Street, dynamited and removed with pick and shovel by children and men in the 1860s to create the dead-end of a train station – a branch line that extended from the tentative city of Melbourne, to the swamps and industry of the docks.

There are the dutiful civic deposits of landscaping, facades and public art (somewhere to sit, something to distinguish your building, something to look at) but no graffiti, posters, self-sown plants or litter to indicate any cultural preoccupations in the site besides eating, shopping and living quietly in an apartment. It is a locale, but it doesn’t feel like anyone’s local.

As an artist, the site represents neither nature nor the fascinating midden of urban life. The city hyperbolically expands, forced to its outer limits by the pressure of density. It uncoils like a Nautilus shell, pushing out from a tightly packed centre to an ever expanding series of larger and larger chambers that represent both luxury and emptiness, high-density and isolation.

inside & outside

Artists have historically most often inhabited marginal urban spaces - lofts, warehouses, rooms above shops, in basements and alleyways. Artists are inside, outside, over and under buildings. Rent, space, light and proximity to resources are definable factors for decisions made about where to make art, to be artists and to show art.

Less definable is the cachet accorded to places that are cool, the desirable aesthetic of creative spaces. Part of this is that sites close to the city and located in city fringe suburbs represent possible contact with the cultural elite, decision makers, collectors and curators. There is an ecological network of interested parties, those who are invested in the cultural life of the polis, participants who can extend their urban lifestyle to include viewing and making art with the possibility of more immediate reward.

It can be that the integrity of the work is enhanced by the location; which people may have seen the work, how it was part of the culturally recognised significance of the site and its future artistic legacy.

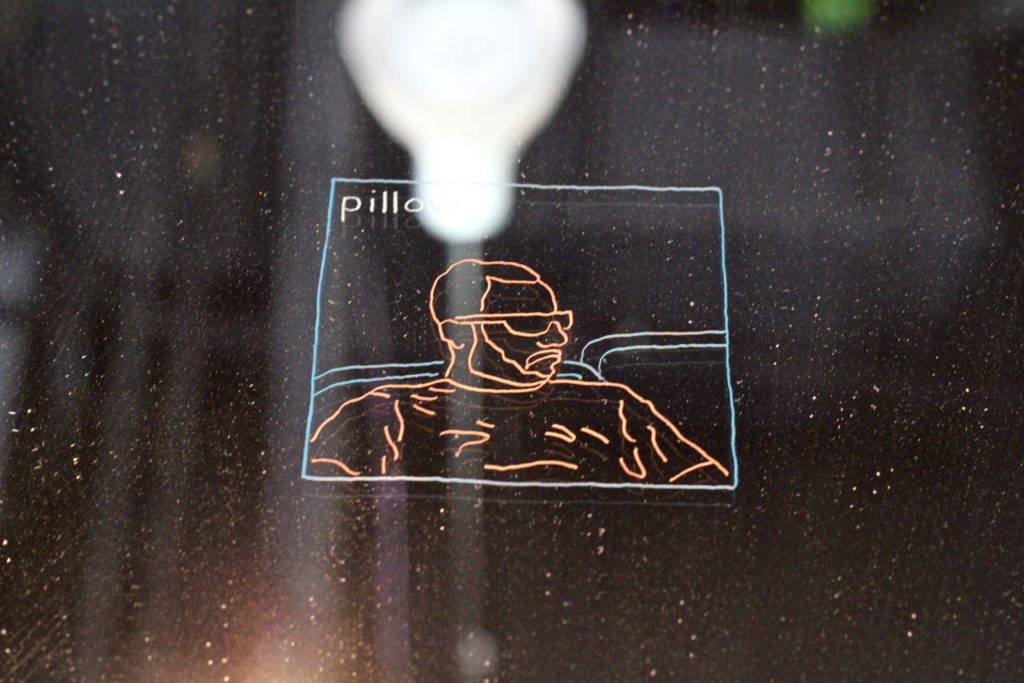

the food court

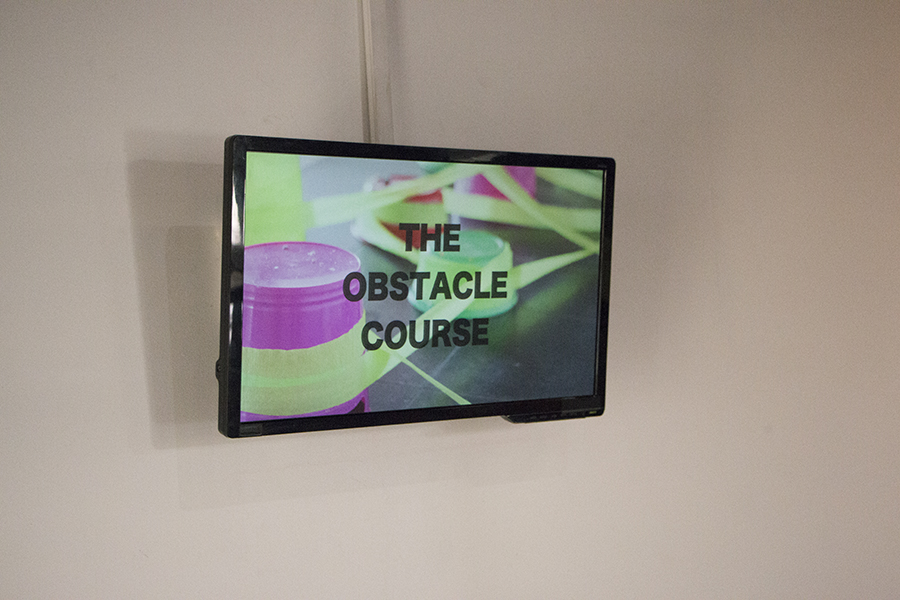

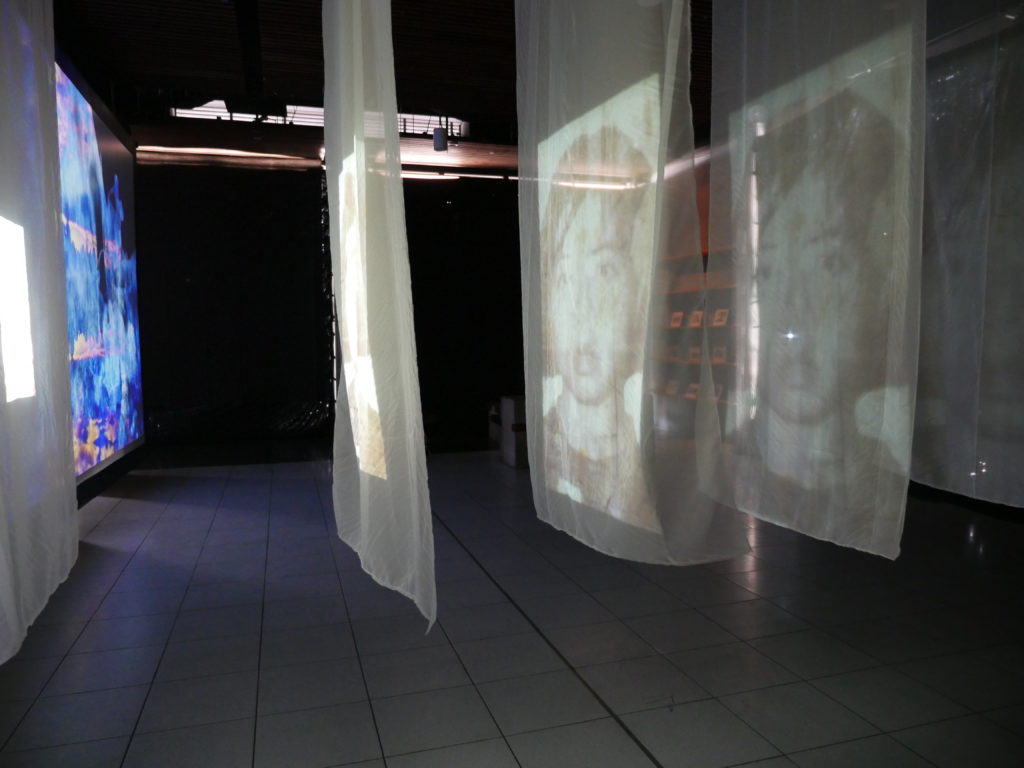

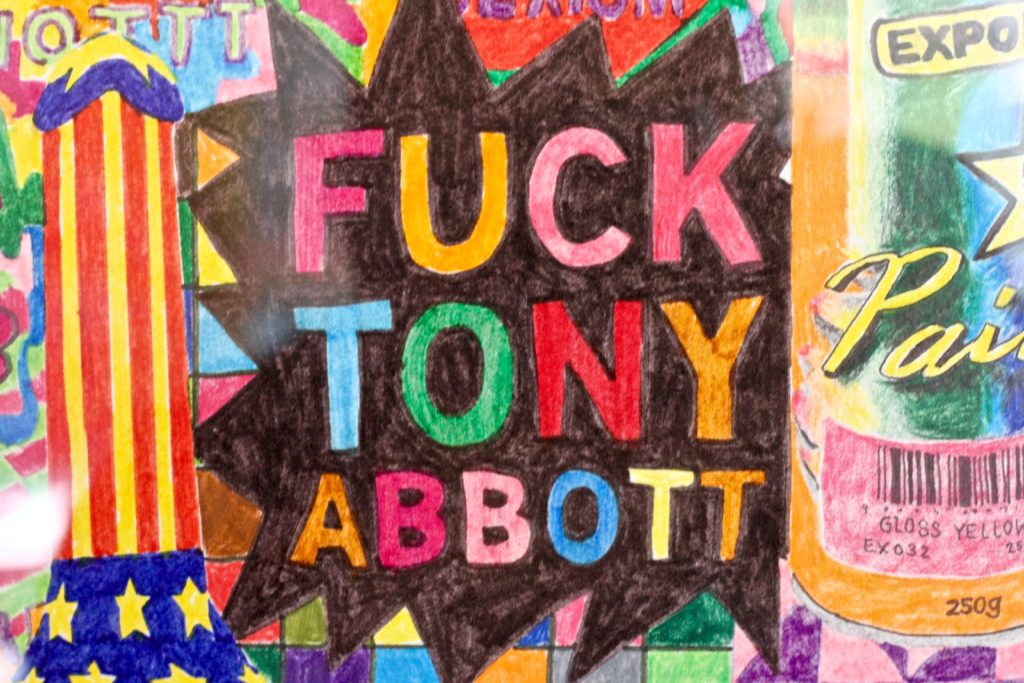

Over the last three years, The Food Court has evolved as a space that lays no claims to the outcomes or nature of the work created, displayed and performed. The curatorial decisions have been marked by consensual agreement based on accessibility, creative use of the space and conceptual risk taking.

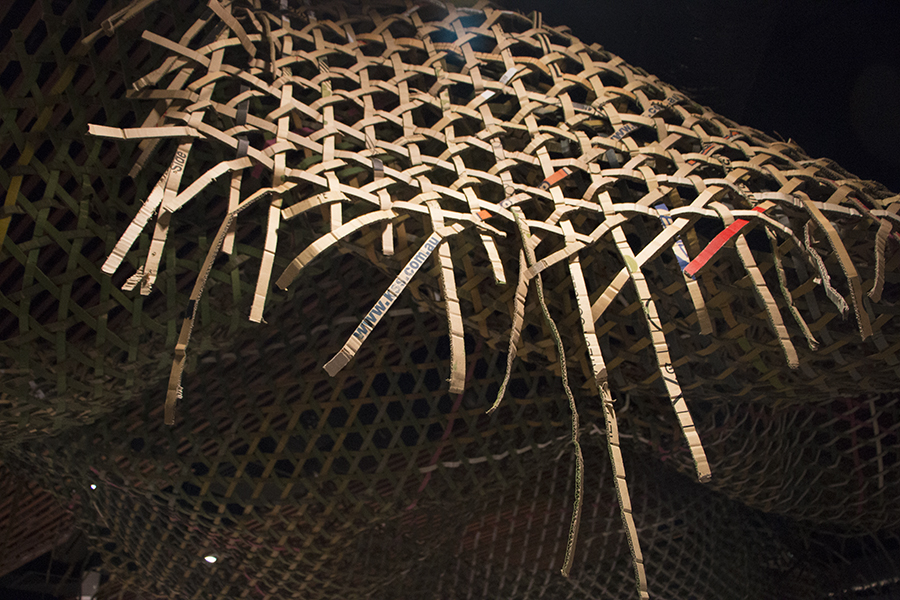

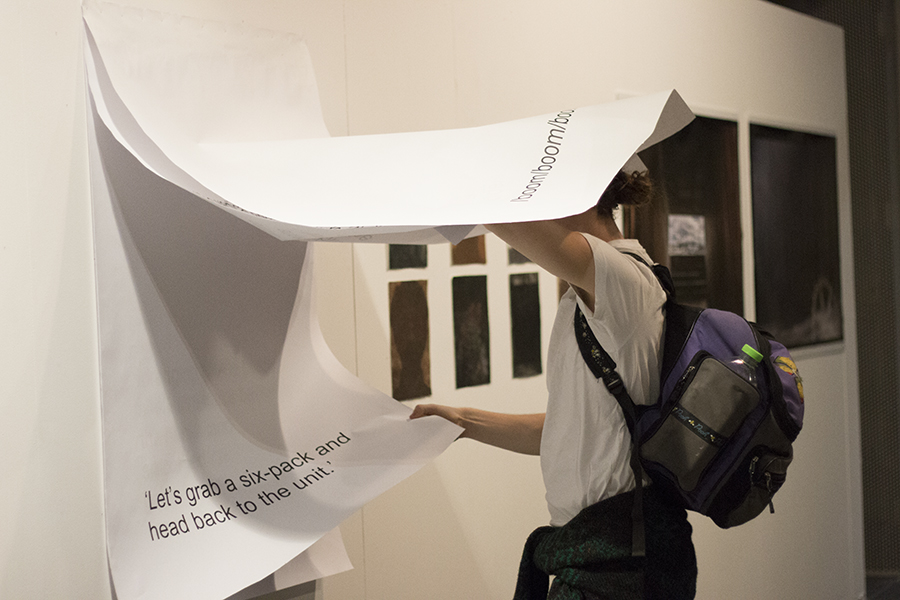

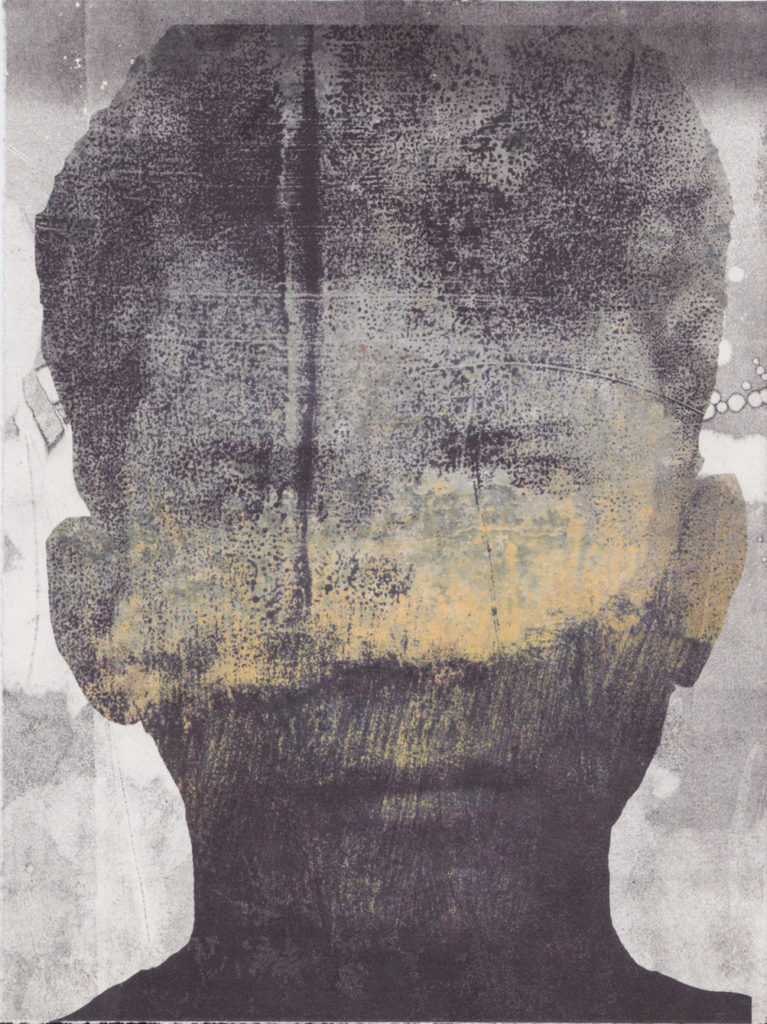

Site responsive work has been mostly represented, the space itself providing a starting point for conceptual work, the site and location has framed conceptual responses to the nature of development, the ethics of industrialised food production, the nature of work and public space and installed pieces that have recontextualised the space (the abandoned Food Court, with it’s existing furniture and signage) or challenged the

interior/exterior binary.

Artists who have developed and shown work in The Food Court represent a

diverse range of ages, socio-economic positions, cultural backgrounds and physical ability and work across mediums, representing visual arts, music, sound, dance, theatre, literature, performance art and video/multimedia.

The Food Court has represented a series of transitory creative occupations, dictated by the precarious tenancy of the site. This tenuous existence and the unselfconscious occupation of an outer-edge, non white-cube space has led to a fluidity of purpose, flexibility of use and astounding outcomes.

Words by Megg Minos

Date of article: 10/05/2016

Date of article: 10/05/2016